Suvi Mahonen and her husband Luke and their bаbу, Spencer. Picture: Natalie Grono

Seven years, 31 IVF attempts, an egg bought from Russia ... baby Spencer's arrival to 48-year-old Suvi Mahonen (@suvi_mahonen) in а Gold Coast hospital is nothing short of а miracle. But the experience is becoming increasingly common.

21 January 2023 | The Weekend Australian Magazine | Ву Jamie Walker (@jamiewalkertheoz)

The link to the original at The Weekend Australian Magazine website →

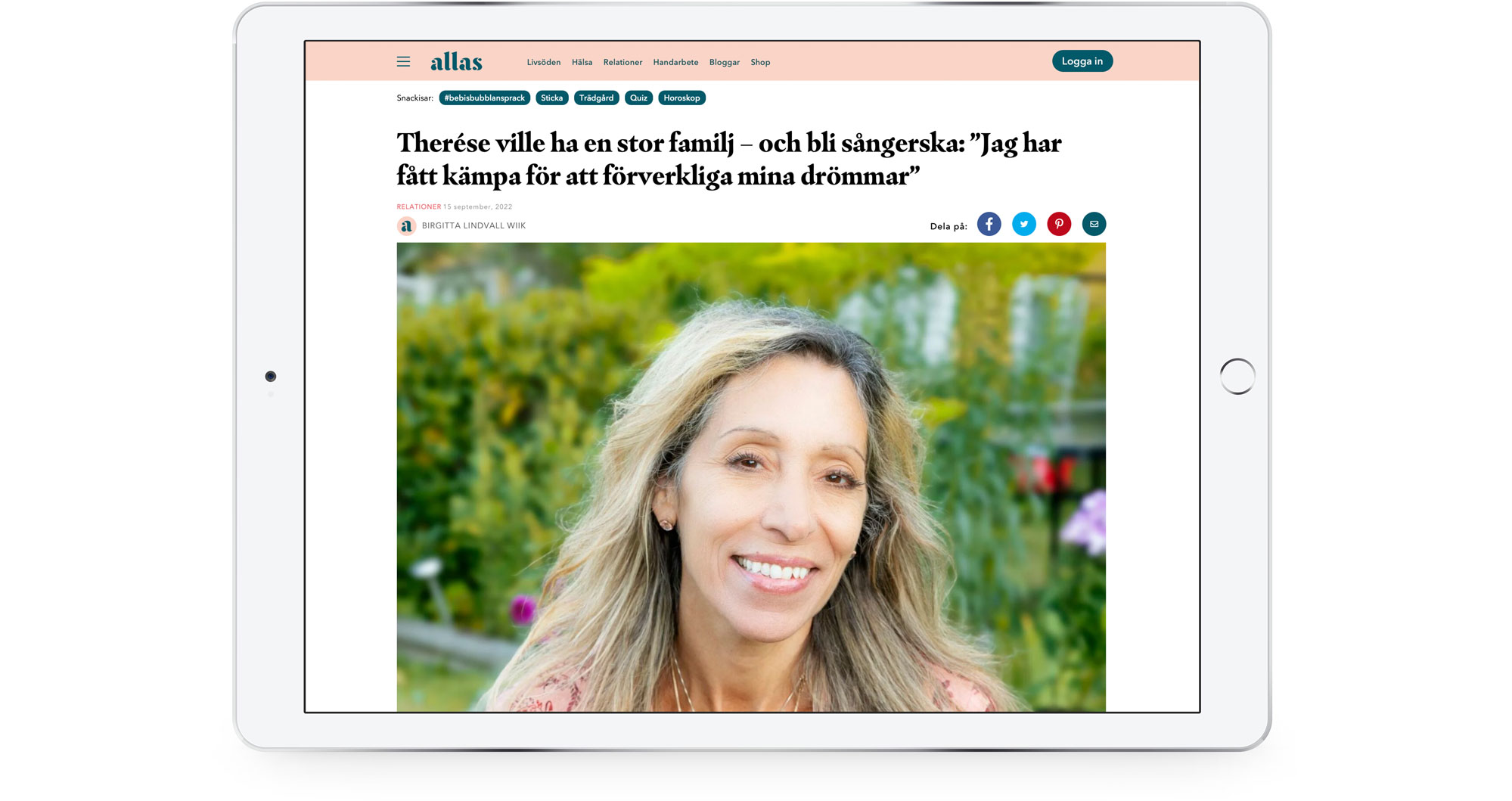

Their blue-eyed boy was to be delivered by caesarean section at 8am on a steamy Tuesday on Queensland's Gold Coast, in a birthing suite that seethed with emotion. The arrival of a baby is always momentous yet in this case it was truly remarkable, bordering on miraculous. Though her belly was numb from spinal painkillers, Suvi Mahonen could feel the obstetrician tugging and pulling, more and more urgently. Her husband, Luke, perched like a hawk over her shoulder, was doing his best to reassure her but there was an edge in his voice - and if he was anxious, that couldn't be good. No, no, no. Surely it couldn't go wrong now. By all rights the pregnancy should never have happened, let alone progressed to this decisive point. Aged 48, Suvi had undergone an unheard-of 31 rounds of IVF in Australia, the US and finally Russia. Count them because she did, over and over again, weighing the disappointment and near-ruinous expense against the mounting odds that she would successfully conceive. "It was nuts," says Luke, 50, and he should know.

To the other expectant mothers in his life Luke is Dr Waldrip, a senior staff specialist obstetrician and gynaecologist at the Gold Coast University Hospital, veteran of a thousand challenging births. Yet today, with the surgical team at work under the direction of colleague Elrich Sem, he is just another nervous father-to-be holding his wife's hand and hoping for the best. True to form, there has been a late complication. Suvi went perilously close to miscarrying at 13 weeks, then developed gestational diabetes and preeclampsia, forcing her to be brought into hospital five days early. There, the baby was found to be in the breech position - head up rather than down - a concern even when the delivery was by C-section.

Ваbу Spencer. Picture: Natalie Grono

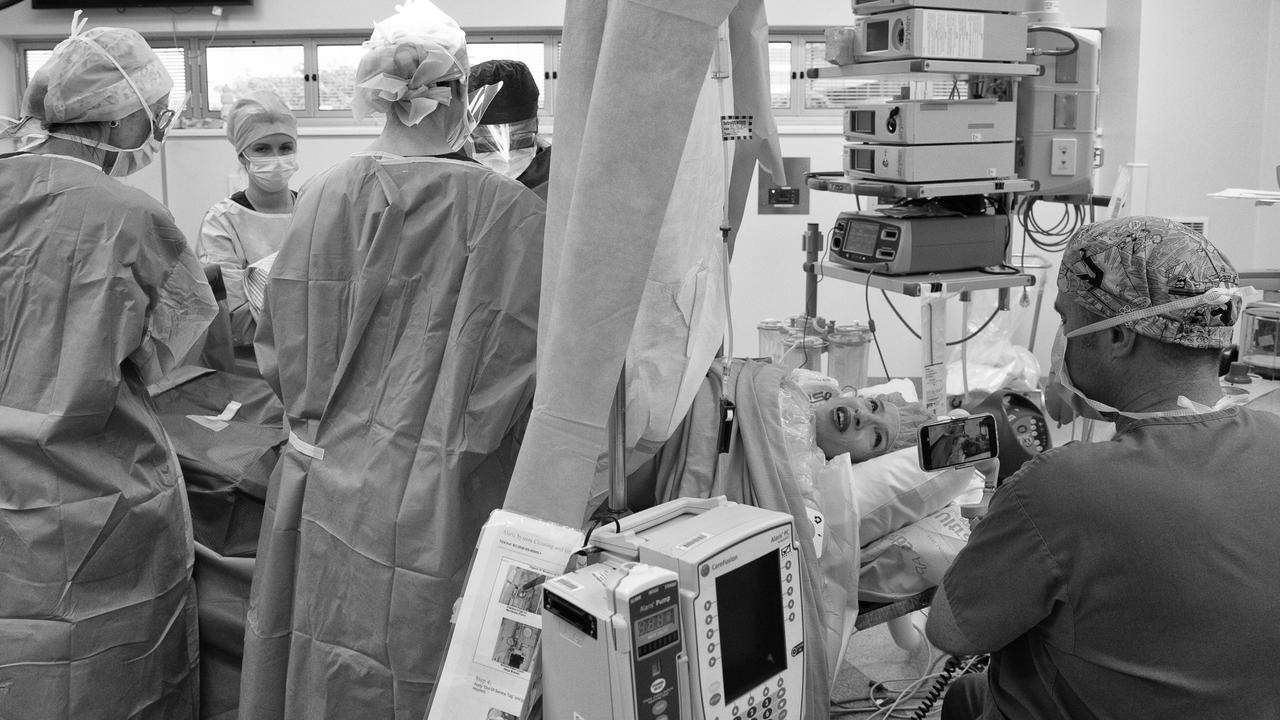

Luke can generally get a newborn out within two minutes of making the first incision. But as the time crawls by - five minutes, seven minutes - Sem has had to resort to forceps to release the baby's snagged head. The tension in the crowded operating theatre is palpable. "What really scared me is the look on Luke's face was sort of getting more and more concerned," Suvi remembers. A freelance journalist, she was never going to let this story pass her by; our photographer, Natalie Grano, is present in the delivery suite along with the couple's videographer.

Fortunately for Suvi, a screen is blocking her view of the operation but she can tell from the dull sensation of the surgeon's strenuous efforts that there is nothing delicate about what is happening. Finally, thankfully, Spencer Harold Waldrip emerges at 10.36am, kicking and crying lustily, weighing in at a healthy 3.3kg. "I can hear him, I can hear him," Suvi says, her voice thick. She reaches out and touches the baby's sticky foot as if to prove he's genuine, that this isn't another of those crushing missteps they've had to endure. Luke's face is wreathed in a broad, relieved grin. "Say hi to Mummy," Sem smiles, lifting the squirming infant high enough for her to see. "There he is," she says. "Oh darling."

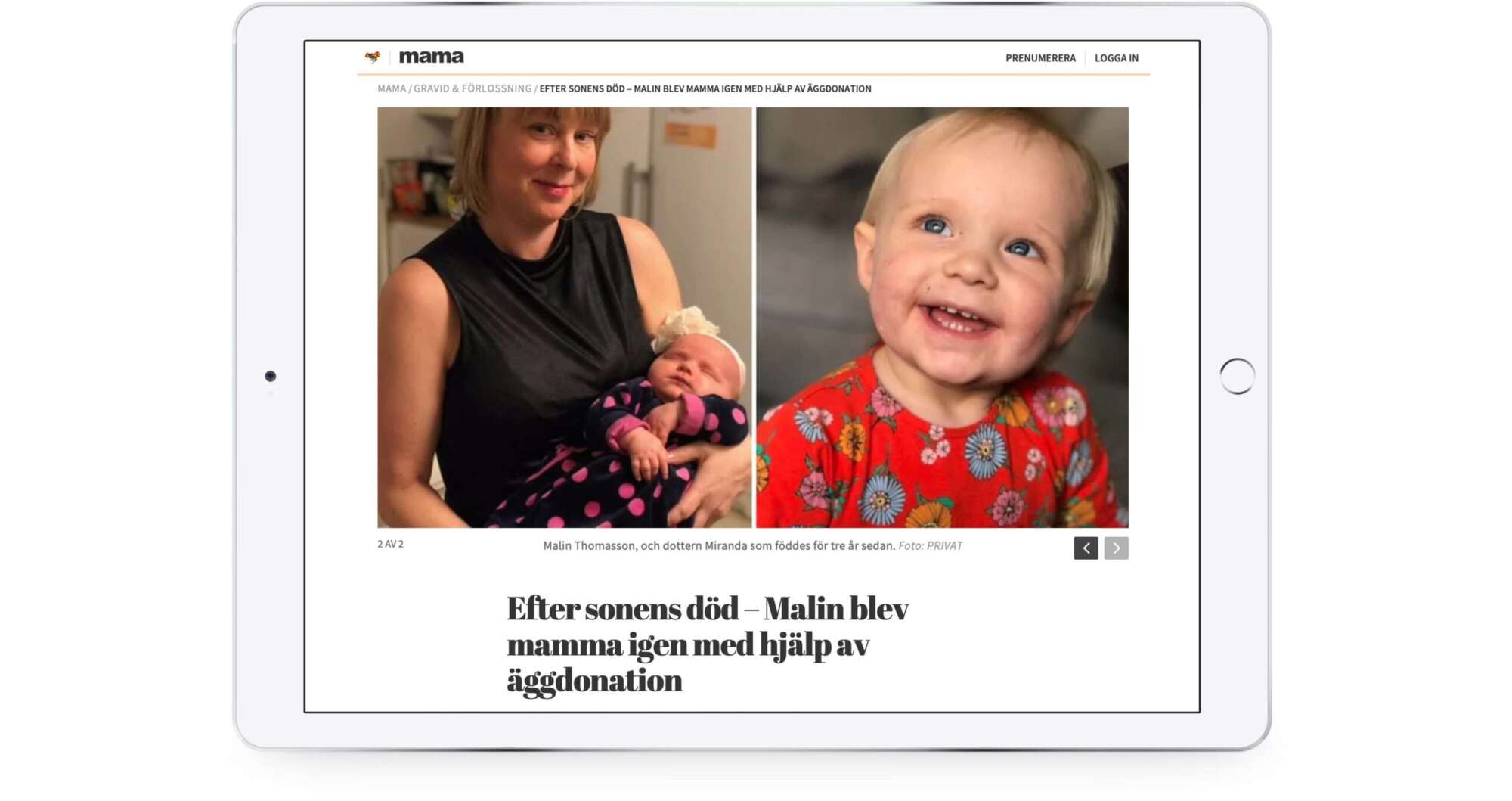

They're all home when we next catch up, the day after her discharge from hospital. Luke looks tired but relaxed in beach shorts while their nine-year-old daughter, Amity, cradles her sleeping brother on the couch. Mum and bub each had their moments after the drama of the birth: she lost 3.2 litres of blood in a post-operative bleed while little Spencer had to be treated for transient tachypnea - wet lung - and low blood sugar. Both are on the mend. Suvi is radiant, her skin aglow. She has to pinch herself that, after everything they've been through, there's an all-too real baby to show for it. What a rollercoaster ride it has been. Looking back, the couple aren't sure how they lasted the distance when the year-on-year grind of fertility treatment was so relentless.

Suvi with daughter Amity. Picture: Natalie Grono

According to a 2021 study by researchers at the University of NSW, 81,000 IVF cycles take place each year in Australia for some 15,000 babies - just on five per cent of all births. The average classroom in this country can be expected to contain at least one child conceived in a glass laboratory dish.

It's a much canvassed function of how we live: with increased education and apparent work opportunities, Australian women like their counterparts in other developed countries started waiting longer to begin a family. In 1981, fewer than 15 per cent of those having their first child were aged over 30; these days, it's more than 51 per cent, the Institute of Family Studies reports. But that has implications for the prospects of a successful pregnancy. To put it bluntly, human eggs do not age well. From the age of 33, the rate of chromosomal abnormality accelerates, tipping 80 per cent by a woman's 40th birthday, studies show.

Suvi and Luke's experience is increasingly common. While they married early -she was 21 - travel and careers were prioritised over children. "The honest truth is we weren't that ducky for many years," she says. "We thought, 'well, we've got plenty of time,"' which might have been true for him, but not her. "For us women, evolution hasn't caught up with the way we want to live our lives," she continues. "We had to learn that the hard way."

By the time they got serious about getting pregnant, Suvi was 35 and having fertility issues. She took Clomid, an estrogen booster to aid ovulation. The drug worked. Her once-regular period, however, didn't return after she gave birth to Amity, an ominous sign in retrospect. Another two years went by before they decided their little girl needed a sibling.

Clomid wasn't going to help given Suvi's misfiring menstrual cycle. In 2015 they launched into IVF full of hope and, of course, trepidation, because if anyone understood the precarious risk-reward ratio it was her husband. Both were insistent about using their own genetic constituents - his seed, her eggs. The problem was Suvi's ovaries were now deeply compromised. Strike One.

They weighed the near-ruinous expense against mounting odds she'd conceive.

They travelled to Melbourne to start IVF treatment. Through round after painful and taxing round, the eggs that could be harvested proved unusable: when fertilised with Luke's sperm and reimplanted, the embryos did not take. To make matters worse, Suvi's bowel was agonisingly perforated by a probe during one procedure. The couple decided to head to the US, where they'd had six embryos chromosomally tested. The man in the white coat at the pricey Los Angeles clinic shook his head when Luke asked about their viability; all were grossly abnormal. Suvi went numb. Given Suvi's fertility issues, they should think about using donor eggs, the doctor said gently, because her own were never going to work.

Instead, sticking with their preference to use their own sperm and egg, they doubled down. The more eggs collected, they reasoned, the better the chances of turning up one that would stick. On round nine they lucked in: 10 specimens, potentially enough to produce six or seven embryos. But when the lab results came back, Luke's hesitancy on the phone was telling. Surely one of them was viable? Suvi asked. "None," he said.

Being prepared for C-section. Picture: Natalie Grono

They pressed on, burning through cash. IVF Australia puts the cost of a round at $10,275, about half of which is rebated through Medicare. Suvi doesn't know how people without their means could afford multiple attempts. Even with Luke's generous salary, they struggled. Their cheerfully cluttered unit in Surfers Paradise is hardly a dream family home, she says, pointing to the gleaming waterfront properties across the Nerang River. "We don't own a second car, we don't take overseas holidays and we certainly don't live in a mansion like one of those," she says. "I'm not complaining. We're lucky we could afford to go as far as we did with IVF. But we sacrificed a lot along the way."

Spencer's nursery. Picture: Natalie Grono

By 2019, round 26, they had reached a decision. After each pickup procedure, conducted under a light anaesthetic, the recovery nurse would write on the back of Suvi's hand the number of eggs retrieved. There was no figure this time, which meant zero. "My ovaries had totally given up," she says. Strike two.

OK, they would go with a donor. The question was, how? Under Australian law, no money can change hands: the process is altruistic, meaning the egg-giver can have her out-of-pocket expenses met, but must not profit from the arrangement. Some people turn to a relative or friend, unavailable to them. Their options were to import frozen ova from overseas, travel to an international clinic or find a good Samaritan here. In the end, they posted on a closed Facebook group, Egg - Donations Australia, hoping for a match.

The initial responses were underwhelming, to say the least. One Sydney woman said she would love to be able to take regular holidays at the beach to see "her kid". As they discovered, the expectation of an ongoing relationship was common among donors. Suvi chooses her words carefully, conscious that she doesn't want to seem ungrateful. "You'd see on the Facebook site where they're talking about the donors and saying things like, 'Oh, they don't need much, maybe a yearly card and photos of the child every so often, just so they feel part of it.' I get it, that's not much to ask at all when you consider what they are prepared to do for us. But this is our family. And remember, I don't know this person and I don't necessarily want to spend the rest of my life dealing with a person I don't know ... giving them some sort of sense of ownership over our family. We felt uncomfortable about it."

Luke filming Suvi during the C-section.

Picture: Natalie Grono

They were looking abroad, feeling more bruised than ever, when midwife Leeah Flynn reached out. A kindly woman of 37 from Kingscliff, northern NSW, with five sons of her own, she was moved by Suvi's honesty. "I knew she was never going to give up until she had a baby," Flynn says. Right off, Suvi felt they were in sync: "Leeah was different. She said, 'I've got everything I need', she didn't want anything from us." The last of her reservations fell away when Flynn forwarded an article about epigenetics - how the birth mother always puts her imprint on a baby, down to fingerprints, regardless of the conception process.

On December 9, 2020, Suvi was about to throw the pregnancy test stickin the bin when she noticed the faintest of pink lines. Could the second embryo grown from Flynn's donated eggs have done the business? After all the disappointment, she wasn't about to get ahead of herself, and just as well. Follow-up tests showed it to be a false positive.

They imported a batch of seven frozen eggs from the US at an eye-watering cost of $27,000, but only five thawed. One of the remaining eggs failed to fertilise, and just two of the four subsequent embryos started mitosis, cell division. A lone survivor made it to day two. "It only takes one," Luke told her and for a while it looked like this could be it: an eight-cell blastocyst on day three, a promising morula of 16 cells on day four. She was getting ready to leave home for the clinic on day five, transfer day, when the phone rang. "I'm sorry," he said. Strike three.

Suvi didn't feel a thing when he slid the scalpel across her abdomen. "Is he out yet?" she asked. The minutes felt like days. "And then I heard Spencer cry."

Luke's friend Alexander Polyakov, an IVF specialist in Melbourne, suggested they try Russia's O.L.G.A. clinic - the eponymous preserve of St Petersburg obstetrician-gynaecologist Olga Zaytseff, who pithily advertises a full refund if treatment fails - "our livebirth guarantee assurance". Before Covid-19 closed the international borders in 2020, Luke had been running the ruler over fertility centres where donor-based IVF is legal in Cyprus, Greece, the Czech Republic and South Africa. (Their budget could no longer stretch to the US, at four times the cost.) Zaytseff's money-back guarantee clinched it, not only financially. Luke saw it as a vote of confidence in the service she offered. Her professional bona fides checked out, as did the refund offer. Of the 750 patients who took out reimbursable packages in the five years to October 2022, 474 ended up with a baby, with another 252 either pregnant or undergoing treatment, according to records Zaytseff provided. The remaining 24 were repaid 30-100 per cent of their outlay, depending on when they exited the program. (The magazine independently confirmed such payments to a number of couples in Europe). Luke was reassured that Polyakov had visited the clinic and came away impressed; he began putting together the $65,000 to send Suvi.

She arrived in St Petersburg on a snowy Thursday in January 2021, relieved to be met at the airport. Located in a stately building on Nevsky Prospekt, facing the czars' famed Kazan Cathedral, the place was shiny and new, staffed by unhurried English-speaking nurses and doctors. The IVF regimen was different from what she had experienced before, starting with an intensive workup with progesterone gel and oestrogen patches to ready her body. "They really throw the book at you in Russia," she says.

Suvi reaches for Spencer after the birth.

Picture: Natalie Grano

She flew home to continue the preparation, injecting herself daily with progesterone in a "training cycle" ahead of implantation. A paid Russian egg donor had been found, something Suvi and Luke were on board with. "I just think it's a simpler, more straightforward process," he says. They returned to St Petersburg together on March 13 for the procession of tests, scans and procedures that they knew all too well after 30 rounds of IVF. Following the embryo transfer, rated a prime 4AA by the attending specialist, Luke carefully studied images of the growing blastocyst, telling his wife the difference from the previous attempts was "profound". Back on the Gold Coast, Suvi took a pregnancy test on April 4: two lines, pink and solid. Her spirits soared.

Thirteen weeks later she was lying on the bathroom floor at

midnight, listening to her blood gurgle down the drain. Luke suspected the placenta had ruptured, putting both mother and baby at grave risk. Suvi could hear her husband talking to himself: hold it together, hold it together. "We're losing him," she said. No, no, no.

The ambulance rushed her to Luke's hospital where one of his registrars took charge while he retched into a sink. "I was pretty sure the pregnancy was gone," he recalls. But at last some luck. The placenta had only partly detached, leaving the umbilical cord intact, preserving the baby's lifeline. As if they needed reminding, it drove home that nothing, absolutely nothing, could be taken for granted.

At week 26, Suvi was found to have developed gestational diabetes and the often related condition of preeclampsia, manifested by high blood pressure. She took the medicine as well as medical advice to take it easy while the weeks wound down to her appointment with Sem in the delivery suite. For once, Luke's encyclopaedic knowledge of childbirth was an encumbrance for both of them. Specialists of his seniority deal mostly with difficult cases or emergencies and over the years he had shared with her horror stories of what could and did go wrong, even in seemingly straightforward births. "There are some things you would rather not know," Suvi says.

She hardly slept a wink the night before the C-section, booked for 8am on November 22. The baby was kicking up a storm, probably reacting to the steroids she had been taking to strengthen his lungs, a routine precaution when he was being delivered slightly pre-term at 37.3 weeks. Inevitably there was a delay; some members of the theatre team had called in sick and replacements had to be found. It was going on 10am before they came for her. Suvi broke down when she was wheeled past the cot parked outside her room, complete with a beanie for Spencer and tanked oxygen.

So this was it. The anaesthetist sat her on the operating table to numb her lower back for the spinal epidural. Thank God, the oversized needle went in the first time. Sem confirmed the baby was in the breech position, bottom down at the top of the birth canal. Suvi didn't feel a thing when he slid the scalpel across her abdomen, though she could sense the increasingly insistent surgical manipulations. "Is he out yet?" she asked. "No, not yet," the obstetrician replied tersely. The minutes felt like days.

"And then I hear Spencer cry," she says, reliving the magic of the moment. "My hands are up ... it's like I'm reaching for him. I can hear him but I can't see him yet. They start to lower the screen and I'm trying to touch him. Erlich is saying

'not me, just the baby' because I can't break the sterile field when he's still operating. Someone is guiding my hand and I feel it - I'll never forget it - this little rubbery foot covered in blood. That's when I know it's real. Luke is touching him as well. Words can't really express the emotion in the room at that time."

One final hurdle. A midwife scooped up Spencer from where he lay on his mother's chest, concerned by his breathing, and handed him to the waiting paediatric team. In a vaginal delivery, the baby is literally put through the wringer, squeezing amniotic fluid from the lungs. With transient tachypnea an excess of retained fluid causes respiratory difficulty, a relatively common complication of caesarean births. Fortunately, it's readily treatable and Spencer soon came good. A low blood sugar count, exacerbated by how hard his lungs have had to work, also ticked upward. He was out of the woods.

Not so Suvi. She lost nearly half her blood volume in the postpartum haemorrhage that kept her in hospital for the best part of a week. Spencer went from strength to strength, feeding hungrily and gaining weight.

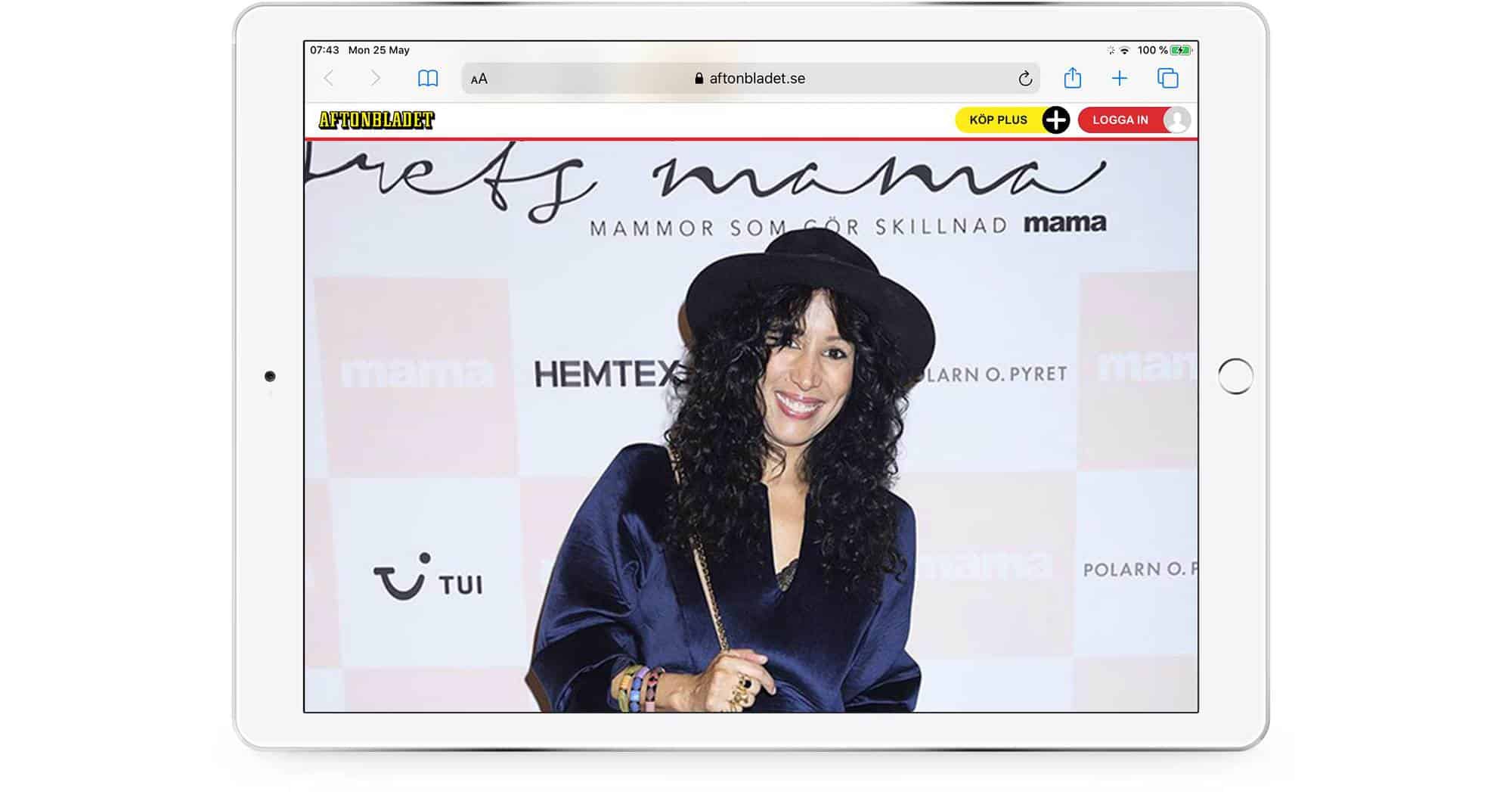

Now that they've all settled in at home, it's time to take stock. Suvi and Luke say they'll never know exactly how much they spent to have their "miracle" baby - her term - but it's well north of $250,000. The expert consensus is they would probably hold the world record if the Guinness people had a category for IVF. Zaytseff says the closest case on her books is that of a 42-year-old Swedish woman who underwent 28 rounds before giving birth last year.

Luke generally counsels his patients against continuing beyond а seventh unsuccessful round of treatment, reasoning: "If it doesn't work bу then, it's рrоbаbу not going to." Why did they press on? "It was the boss's call," he says with а smile. Suvi admits their thinking wasn't always logical. "Once you get on the rollercoaster it's very hard to get off," she explains. "You live in hope that it will work next time ... that you just have to get something out of everything you've put in."

Suvi moments after Spencer's Ьirth.

Picture: Natalie Grono

Most notably, if they had their time over, the couple would have sought out an egg donor sooner and gone abroad. The system in Australia is stacked against IVF users, they believe. As well-intentioned as altruistic giving is, the pitfalls are acute, compounding the already heavy financial and emotional burden of fertility enhancement. And if Zaytseff can guarantee а live

"Australia's IVF laws are sadly outdated and make it very difficult for couples, especially as Australia is isolated and so travel to countries where, say, donor egg IVF is much more accessibe is extremely costly," Suvi says. "That and the fact that some of the laws just don't make sense." She points to the jarring disconnect in the importation of fertility products. "You can ship frozen sperm and frozen eggs into Australia, but you cannot ship your own frozen embryos even if they are created from your own egg and sperm into the country."

Strict regulations around egg donation in Australia exist, it is usually said, to prevent exploitation of women. But, Suvi says, "the fact that egg donation must bе altruistic in Australia sets up what I believe can in some cases bе the wrong dynamic between women donating their eggs and their recipients, with recipients feeling emotionally beholden to donors who have the upper hand in the exchange. А simple monetary transaction for eggs seems а more honest and fair exchange."

Luke's personal and professional advice is to get cracking if you want children: "Don't bе delusional about your fertility. It's unfair that it mostly falls upon the female, but that's just the way it is," he says. If you are genuinely happy with only one or two children, then start trying bу the time you're 33 and if you want а bigger family then start bу the time you're 30. Professionally, 1 see а lot of women in their late 30s and 40s who left it too late."

Suvi looks on, nursing the bаbу. When he's old enough, they will take him through where he came from, the ups and punishing downs of their IVF odyssey, and if he wants to meet the egg donor they will try to make that happen as well, though it's not currently allowed in Russia. Their blue-eyed bоу and his darling sister will know all of it because it's the story of the family they went to the ends of the Earth to create. Yes, yes, yes. It was incrediby worth it.

The link to the original at The Weekend Australian Magazine website →